Harley-Davidson Introduces All New 2018 Softail Line

The Dyna and Softail lines, as you know them, no longer exist - These Are Better!

When Harley-Davidson released its updated 2017 touring line with the new Milwaukee-Eight engine, it didn’t take any insider information to figure out that the new powerplant would eventually propel all of Harley’s Big Twins. Well, that time has arrived with the announcement of the Motor Company’s 2018 model lineup. While the engine upgrade itself isn’t much of a surprise, the way HD chose to craft an all-new Big Twin chassis around the Milwaukee-Eight is huge news. We’ll let Paul James, Manager, Product Portfolio for Harley-Davidson explain:

“In model year 2000, when Softails got the Twin Cam engine, the mantra was ‘We changed everything without changing a thing.’ Those bikes were all new and different, yet they cut the same style and look as the bikes they replaced. That was not the intent here. Our intent was to move this design language along.”

And design isn’t the only thing that changed. We’ll just get to the point and repeat the subhead of this article: “The Dyna and Softail lines, as you know them, no longer exist.” In fact, the Dyna line doesn’t exist in any form at all.

Pause and let that sink in for a minute.

Dyna lovers shouldn’t fear the loss of their favorite models, though. Each Dyna model still exists, only it’s been subsumed by the Softail line. Now, before you go jump on your beloved Dyna and ride off into the sunset, screaming about the heresy, leaving us with little more than the smell of tire smoke and a lingering vision of a raised middle finger over some dual shocks, read on. You might just find that what the artists and engineers at the Product Design Center (PDC) have done for the performance-minded Harley riders actually suits your tastes. Then, immediately go book a test ride.

Starting from (almost) scratch

With a company that values its history as much as Harley-Davidson does, nothing is ever designed from a truly clean sheet. That said, the changes required to merge the Milwaukee-Eight engine into the existing product line’s chassis provided a unique opportunity. The company could behave as it had done in the past by making the new bikes look like nothing had changed, or the designers and engineers could capitalize on the designs of the past as they look to the present and the future. This time, Harley chose the harder, riskier path, deciding to undertake the largest product-development project in the motor company’s history. Once the project was complete, eight new models plus four larger-displacement variants would be ready for the riding public.

The driving tenets of the Softail program were: incorporate the new powertrain into the chassis; improve the dynamic capability of the entire H-D cruiser line; deliver more comfort to the rider and passenger; and reduce the weight of each model.

Fitting the new engines into the frames while losing weight sounds pretty self-explanatory – if that is all you’re doing. Improving the line’s dynamic capabilities, however, requires comprehensive updates aimed specifically at handling, lean angle, and suspension capabilities. Similarly, rider/passenger comfort covers everything from engine heat to suspension compliance. There simply wasn’t one easy or clear path.

Engine Changes

Although the Milwaukee-Eight engine has a purported 75% less vibration than the Twin Cam (as we noted in our 2017 Harley-Davidson Milwaukee-Eight Engines Tech Brief), the touring line that first received the engines uses rubber mounts, but that level of vibration would be too great for the frame-stiffening and rigid mounting planned for the Softail chassis. So, while the engine is largely the same, having the same rotating assembly, crankshaft, pistons, heads, etc., a second counterbalancer was added to the Milwaukee-Eight for Softail use. Now, twin counterbalancers mounted on each side of the crankshaft rotate in the opposite direction to the crank itself, quelling vibration.

2017 Harley-Davidson Milwaukee-Eight Engines Tech Brief

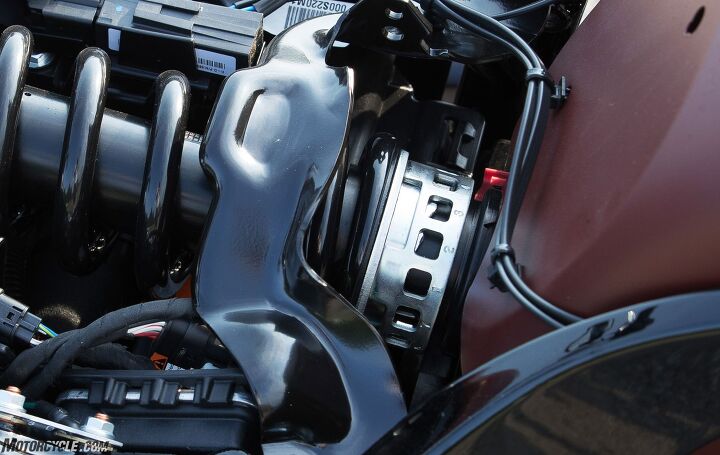

Unlike some of the liquid-cooled M-E touring models, only oil/air cooling will be offered on the Softails. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, since the radiators of the Twin-Cooled engine reside in the touring bikes’ lowers – items that none of the Softails have. Instead, a well-hidden trapezoidal oil cooler takes up residence between the frame downtubes. Assisting in keeping the lines around the engine clean, the hoses feeding the cooler are routed so that they are virtually invisible from a distance.

Perhaps the biggest change to the Milwaukee-Eight is the switch to a wet-sump design which negates the need for an oil tank under the seat. This change yields several benefits. First, it moves a heat source and potential cause for rider discomfort down to the bottom of the engine. Locating all of the oil under the engine also lowers the bike’s center-of-gravity and helps with the handling goals. Finally, since much of the suspension is now under the seat, room was needed to house the battery and electronic components in the smaller space.

One platform to rule them all

The planning team at Harley-Davidson knew the Dyna and Softail lines attracted different kinds of customers. The Project Rushmore-developed research they conducted, where they literally went into riders’ homes and garages to talk motorcycle likes and dislikes, revealed that Dyna owners had “self-selected” themselves based on the differing performance attributes of the Dyna line.

“The way they rode their bikes was a little bit different from the average Softail customer,” noted James, meaning they valued better handling and more lean angle – you know, the dynamic capability that was one of the stated goals of the Softail project. Of the two platforms, the Softail was always the prettier one. Keeping this goal in mind, James stresses that the new platform was “marrying the best of both worlds: the best attributes of Dyna with the best attributes of Softtail in this platform.”

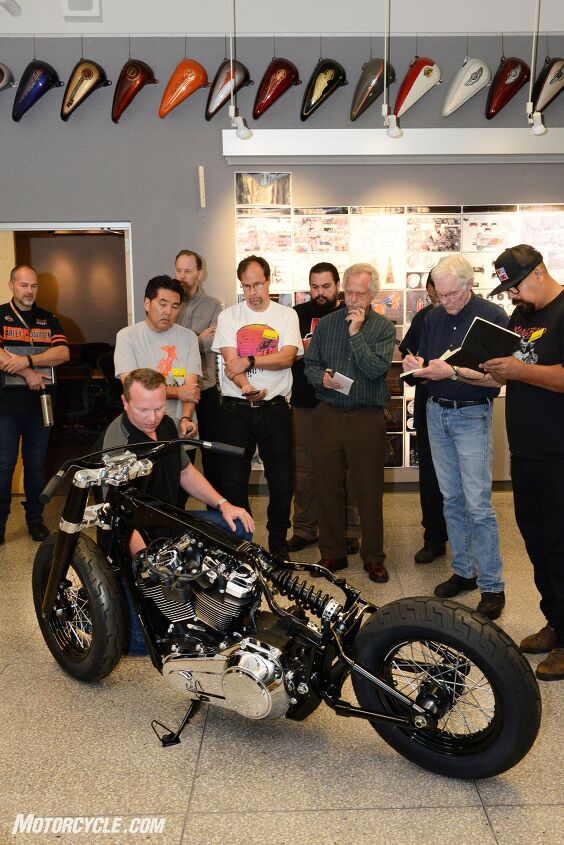

Throughout the design process, a 1950 FL stood as inspiration in the Harley-Davidson Styling and Design Studio.

“That motorcycle, in particular, really does show some of the bones that we were trying to capture with the development of the new Softail platform,” said Brad Richards, Vice President, Styling and Design. “We wanted to make sure we didn’t lose any of that original DNA…. We had to make sure we could deliver that esthetic.”

A close look at the new Softail shows how true to the bones of the hardtail frame the project is. Note the visible space between the cylinders and the frame in both the old and new motorcycles. Then, for a point of reference, look at a Twin Cam Softail.

Motorcyclists are well acquainted with how a solid-mounted engine helps increase a frame’s stiffness, but riders may be surprised to learn that it can also help with other tolerances, too. For example, a rubber-mounted engine will move around inside the frame it is mounted in, requiring more space to swing its elbows without bumping into things. A rigid engine allows for tighter margins.

“The way the motor is framed within the frame is really important,” Richards explained. “We didn’t want a lot of excess space around it with a lot of light coming through. We really wanted to make sure we had a tight composition between frame, motor, and componentry. So, the rigid-mount helped us do that.”

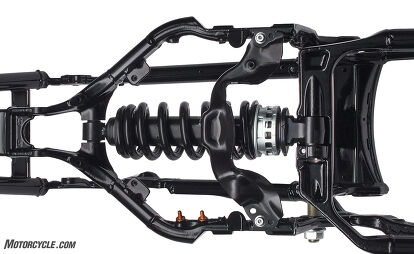

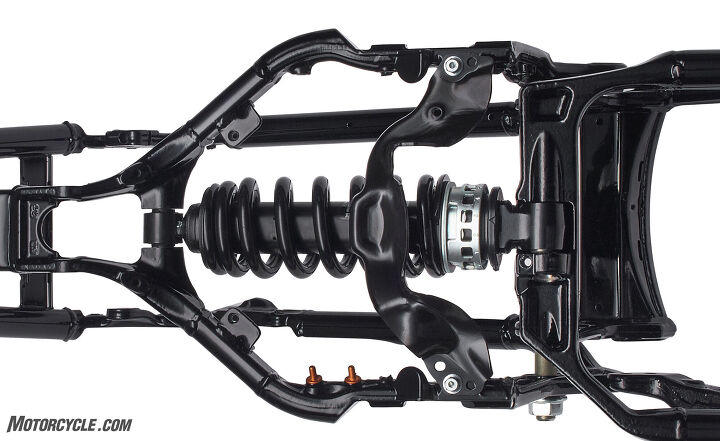

While the style of the chassis/engine combination was important, the primary factors affecting the new frame’s design were performance related. The redesigned Softail frame is 65% stiffer than the previous one, and if the stiffness is calculated from contact patch to contact patch, the resulting improvement is 35% – that’s after passing the forces through the steering head and the swingarm pivot. The new frame features 50% fewer parts and a 22% reduction in welds, making it easier to manufacture. The rear suspension loads are transferred from the single shock directly up the backbone of the carbon steel tubular frame, which eliminates any twisting or bending forces that would have required more complex (and heavier) gusseting. The new frame also gave the shock a longer stroke to handle its absorption duties by improving the wheel travel to shock stroke ratio by more than 70%.

In the end, the new Softail line chassis consists of three different frames, consisting of 28°, 30°, and 34° steering head angles. Additionally, one swingarm is used to accommodate a 240mm rear tire while another is used in all the other tire sizes.

New suspenders

The old Softail had dual extending shocks under the frame – a location that made it difficult to adjust the preload to accommodate variances in loading. Consequently, riders mostly left the dual shocks at their factory setting if they knew it was adjustable at all. While this might be fine when riding solo, adding a passenger and/or luggage, or even an American-sized man with an aggressive riding style, could eat up a large percentage of the suspension travel before encountering any road imperfections. So, the developers saw easy adjustment of the rear preload to be more than just a handling issue; it was a rider/passenger comfort issue.

The new, under-seat location of the Showa monoshock makes it possible to easily adjust preload as required. To maximize the benefit, Harley made the preload adjustment capable of spanning a 240-lb. range in passenger/cargo weights (which, in some cases, more than doubled the rated load the bike could carry). Depending on the model, the rider can adjust preload through either a ramped collar, an under-seat hydraulic adjuster, or an external hydraulic adjustment knob.

The new shock position and rear suspension geometry deliver a rear wheel travel to shock stroke ratio of about about 2:1, and the shock stroke has increased to 43mm, giving Showa more stroke to work with for handling bumps. Aside from better control of the rear-wheel movement, the longer strokes allow for a softer stop when the suspension bottoms. Fun fact: two bikes (the Heritage Classic and the Fat Bob) received dampers with 56mm of stroke and the associated increase in rear-wheel travel, but before you ask, these longer shocks will not be available as accessories for the other models.

All of the new Softails, save one, received Showa’s dual bending valve forks that we first sampled and enjoyed last year in Harley’s touring motorcycles. The advantage of the dual-bending technology is that it allows tuning over a wider range of conditions. Previously, the proper balance between comfort and chassis control was more difficult to achieve and usually required compromising one of the options. The dual bending valve allows for the generationt of more low-speed damping and separate control of the high-speed damping’s ability to absorb big hits. The lone exception to the dual bending valve fork, the Fat Bob, utilizes an inverted cartridge fork.

Get your lean on

Here at MO, we’ve frequently been pretty hard on Harley-Davidson for hamstringing many of their model’s capabilities via limited ground clearance. Well, one of the major ways that the artists and engineers in the PDC wanted to improve the Softail’s dynamic capabilities was through increased lean angle. Every part that could conceivably play a role in increasing cornering clearance was created with this in mind. For example, when the engineers designed the floorboard support brackets, they had strict foot placement and cornering clearance planes relative to the engine and chassis and required that the bracket supporting the floorboard fit within the wedge of space created by those three fixed planes. Oh, and the bracket had to look good, too. The dance between the designers and the engineers yielded organic-looking mounts that met their strength requirements by utilizing forged aluminum which also delivered a nice weight savings, too.

However, the changes to cornering clearance didn’t stop with the easiest places, like the pegs and floorboards. The engine’s primary cover has always been a limiting factor in the left side’s lean angle. Since the engine’s crankshaft had to stay in the same relative position within the frame to maintain the Harley look, raising it in the frame wouldn’t work. Rotating the back of the engine upwards to gain clearance would change the angle of the cylinders’ V, making that a non-option. So, the solution ended up being a change to the interface between the engine’s cases and the transmission to allow the primary to lift a tad higher.

While the lean-angle specifications reflect the fruits of their labors, the engineers and the PR folks all insist that the SAE numbers don’t truly reflect the increases they were able to achieve in real-world scenarios. The SAE standard for measuring motorcycle lean angle requires that both the front and rear suspension be compressed 75% prior to taking the measurement. The real world instances in which this set of conditions would occur are relatively rare, compared to other cornering scenarios. So, the real world increases in cornering clearance are more pronounced than the numbers would reflect.

Trimming the fat

According to Harley, the bulk of the new Softail line lost about 30 pounds of weight compared to last year’s versions. Some of the former Dyna models didn’t lose quite that much, but the differences are still significant. According to the engineers, every part was subject to a weight-reduction goal because the weight of the motorcycle affects every dynamic characteristic of the machine. Any weight loss would improve acceleration, handling, and braking.

The list of how the weight reduction was achieved reads like a parts manifest. The new chassis is 15%-20% lighter (13-18 lbs.) than the 2017 Softail models. The bulky steel exhaust hanger was replaced with a lighter forged aluminum unit saving a couple pounds. The fender supports are now forged aluminum, as are the triple clamps. New fuel tanks shaved weight. Every little bit adds up with the net result being an improved power-to-weight ratio that riders will enjoy every time they twist the throttle.

The all-important styling

People who don’t grok the whole Harley-Davidson motorcycle thing think they are all about style, and on a certain level they are right. Harley, more than just about any other manufacturer, places a huge importance on curating the company history as it plays out in the styling of its current generation motorcycles. Remember, the mantra from the 2000 implementation of the Twin Cam engine: “We changed everything without changing a thing.”

Since a 1950 FL was front-and-center in the designers’ minds when they were creating the new Softail line, the company has not ceased to place styling and history high on its priorities; the list is simply expanding. For example, we find ourselves some 2,300 words into this article about the new Softails, and the bulk of the text has been about how the designers have infused the new chassis with more function. Only now, are we ready to take a closer look at the styling.

The enthusiasts who were tasked with creating the new Softails (and they are enthusiasts) clearly feel the weight of this responsibility. When the conversation finally moved into styling, a demarcation in the model line began to appear. Although not an official marketing term for the line, a group of three models was referred to multiple times as Foundational Standard Cruisers. Richards noted the importance of these models by stating, “If you do those foundational motorcycles correctly, our customers will give us permission to stretch the brand into places they might not have thought it could go.”

The Softail Slim, the Deluxe, and the Heritage Classic form this grouping, and when viewed from a distance, their lines are almost identical to those of the previous model year. However, details start to emerge on closer inspection that point to the bikes being MY2018 models. The engine is more tightly framed within the chassis. Cables and wiring are more neatly tucked away. The oil tank has been replaced by covers over the battery and electronics. The Deluxe becomes a solo seat model and receives LED lighting throughout along with a modern integrated light bar and turn signals. The Heritage Classic, while still maintaining its profile, takes on a darker, more modern style and gains sealed, locking saddlebags that can be easily removed.

The designers took more risks with the remaining five members of the Softail line. Several models look like they have no instrumentation thanks to the new LED panels embedded in the top of the handlebar clamp. While most of these bikes have profiles that will be immediately identifiable to Harley cognoscenti, the designers have taken tremendous liberties with a couple well-loved icons. This is where Richards says the design department is cashing in the chips it earned with the Deluxe, the Heritage Classic, and the Slim.

Yes, at first glance, the 2018 Fat Boy could only be a Fat Boy, but the update is radical. The solid wheels remain, yet they grew to accommodate 160-wide front and 240-wide rear tire sizes. The fenders are bobbed, and the center-mounted brake light has disappeared. The headlight has morphed into a 1950s-inspired trapezoidal nacelle that defies description. Yes, it’s a Fat Boy, but boy, is it different.

The same can be said of the most radical update of the Softails, the Fat Bob. Looking like a mash-up of an adventure bike, a Monster, and a V-Max, the Fat Bob offers the most cornering clearance of all the Softails, with more than 30° lean angle on both sides. Where the Fat Boy looks like a steamroller, the Fat Bob could be the vehicle for riding out the zombie apocalypse. The narrow, rectangular LED headlight looks like it is ready to shoot laser beams. Harley is clearly gunning for a younger, sportier demographic with the Fat Bob. Only time will tell if they succeeded.

A brief ride

Because so much of the development of the Softails was focused on function, Harley-Davidson flew a select group of journalists to Milwaukee to sample the line in a controlled environment. The structure of the ride was brief and information-filled. Over the space of about four hours, journalists rode a total of 20 motorcycles. By the time we were done, we had ridden the entire Softail line of eight bikes plus two 114 cu. in. variants for a total of 10 models spanning two model years each.

The routine was: first, a 2017 model would be ridden and would immediately be followed with the new 2018 version to give a direct comparison. Each stint consisted of two laps around the Blackhawk Farms Raceway with a 0-80-mph acceleration test taking place on the front straight between laps one and two. The test was designed to give a brief sampling of the improved ground clearance and handling along with the upgraded power-to-weight ratio.

Anyone who says they could get more than a cursory impression in approximately four miles of riding is either deluding themselves or is many times more talented a rider than I am. My general impressions are that the Milwaukee-Eight engine is much more powerful than the erstwhile Twin Cam and out-performed it in every way. The 0-80-mph acceleration test not only revealed a smoother, more powerful engine, but also how easy it was to modulate the torque-assist clutch. Shifting from first to second gear usually resulted in a chirp from the rear tire. At speed around the track, the EFI tuning was spot on without any hint of abruptness in throttle transitions. Vibration was minimal until the upper rpm range where the typical rider wouldn’t spend much time. Cruising at highway speeds, the engine had a pleasant vibrational signature.

As you might expect, handling varied by model since wheel size and rake play such a prominent role. The first bike I sampled was a Breakout, a bike I’ve never been particularly fond of riding. Despite its attitude and straight-line badassery, the pegs – or the rider’s heel – on the 2017 model touch down as soon as you think about turning. Even tiptoeing into the corners at the track generated scraping noises. While the 2018 version still had handling influenced by the 18-inch 240mm wide rear tire and the 21-inch front, the ground clearance was noticeably better. The 114 cu. in. variant delivered the performance you’d want from such a dragracing-inspired motorcycle.

The first revelation of what I could expect from cruisers with floorboards came with the Softail Slim. The previous generation dragged hard parts predictably and fairly early. The 2018 Slim, however, surprised me in the first corner. It turned in easier, precisely holding its line, and I didn’t touch the pavement with any hard parts until I went looking for the limits of lean angle.

The Heritage Classic performed in a similar manner, but since it has the taller shock option, I’d expected a smidge more cornering clearance. A quick glance at the spec sheet reveals lean angle numbers virtually identical to the Slim. The longer shock must, in this instance, be directed towards providing better cargo-carrying capacity to suit the Heritage’s light-tourer duties.

Now is a good time to consider what increased cornering clearance means to the new models. The improved lean angle doesn’t mean that Softails have magically become sportbikes. They’re still cruisers with all the limitations associated with the feet-forward riding position – and cruiser riders don’t go around constantly scraping floorboards. They simply don’t ride that way. However, any increase in cornering ability means that riders will have more lean available to them should a turn tighten up on them unexpectedly. This improvement can be seen as a safety feature. For riders who do like to ride at the limits of their motorcycle, more lean means more fun. So, everyone should be happy with the Softail’s newfound capabilities.

From the moment I laid eyes on the new Fat Boy, I was anxious to ride it. How could a motorcycle with a 160mm front tire and a 240 rear do anything other than go in a straight line? I’ll have to admit that the Fat Boy surprised me. At low speeds it was remarkably easy to maneuver. The bulk fell away. However, it requires a firm hand when cornering at speed. The nature of the big tires front and rear makes the bike want to stand up in corners. Give the handlebar constant countersteering input, and the Fat Boy corners remarkably well. As Paul James put it when introducing the Fat Boy, “It handles better than any motorcycle with a rear tire for a front should.” Still, the Fat Boy is clearly a profiling bike and not one riders will be spending tons of time strafing apexes on.

Since the Fat Bob is the most performance-oriented of the Softails, I was most excited about riding it – in both the 107-inch and 114-inch iterations. However, riding on a racetrack and not the open road, I had the most trouble riding the Fat Bob at a street-reasonable pace. The ride is sporty with decent cornering clearance. The beefy tires were remarkably neutral steering, and the Bob didn’t mind having the brakes trailed to the apex of the corner. I could see myself having a fun time romping along a bunch of my favorite SoCal roads. Clearly, MO needs to get a Fat Bob in our possession as quickly as possible.

Let the waiting begin

For 2018, Harley-Davidson has made a bold move with its Softail line. Every performance aspect has been updated to some degree, and from my experience, the dynamic updates were all for the better. Some Dyna diehards will be upset by the end of the line, but since many of them are more performance-oriented riders, they may be won over by a test ride – or three.

The styling changes are the larger risk. While each model has largely stayed true to the lines of the motorcycle it replaces, Harley – and therefore Harley riders – have typically been averse to large-scale change, and large-scale change is what the Motor Company has on the menu for 2018.

Will the new Softails help to fill the spaces vacated by Harley’s core demographic aging out of riding? We’re as yet unable to say for certain, but we’re excited by the prospects that the new models offer and can’t wait for the opportunity to really test them for you. Let us know what you think of the new Softail line in the comments.

Like most of the best happenings in his life, Evans stumbled into his motojournalism career. While on his way to a planned life in academia, he applied for a job at a motorcycle magazine, thinking he’d get the opportunity to write some freelance articles. Instead, he was offered a full-time job in which he discovered he could actually get paid to ride other people’s motorcycles – and he’s never looked back. Over the 25 years he’s been in the motorcycle industry, Evans has written two books, 101 Sportbike Performance Projects and How to Modify Your Metric Cruiser, and has ridden just about every production motorcycle manufactured. Evans has a deep love of motorcycles and believes they are a force for good in the world.

More by Evans Brasfield

Comments

Join the conversation

I like the direction HD is heading, less vibration, less weight. I like LED lights and the new instruments. But, HD does not make a bike for me! I grew up riding dirt bikes and standards. MAKE A STANDARD MOTORCYCLE!!!!

Wow, it's only 2018 and Harley discovers less weight is a good thing! They've certainly got plenty to go at, even my "car on two wheels" BMW K1600GT is lighter than pretty much every Harley bar the 883