2013 BMW S1000RR HP4 Review - Video - Motorcycle.com

If the Japanese and Italian sportbike manufacturers weren’t yet quaking in their boots by the fabulously engineered S1000RR, the HP4 will surely make them fret. The standard S1000RR topped our rankings in our recent European Literbike Shootout, and the HP4 significantly ups the ante of what’s possible with a street-going superbike.

Just five years ago, the idea of BMW building a supersport literbike that could manhandle the class’s established players would’ve been a fanciful one. But that’s exactly what happened. It took class honors in our 2010 Literbike Shootout, and several subtle revisions for 2012 added up to significant improvements when we tested it at its launch in Valencia last fall.

Less than one year later we’re back in Spain for the HP4’s launch, this time at the Circuito de Jerez, home of the Spanish Grand Prix. Never has a bike this fast been so easy to ride.

What’s In a Name?

The HP4 is the fourth model in the series of HP bikes kicked off in 2005 with the introduction of the HP2 Enduro, a high-end version of the R1200GS. The Boxer-powered HP2 line was later joined by the HP2 Megamoto, a supermotard version of the Enduro, and then came the roadracing-oriented HP2 Sport Pete rode in 2007. Consider the HP sub-series like BMW’s M automobile division.

To bring the S1000RR into HP territory, it’s fitted with a bevy of hardware and software upgrades. In the hardware section, aluminum wheels are now created by forging instead of casting, which results in lighter 7-spoke wheels. Together with a lighter sprocket carrier, the HP4 shaves a considerable 5.3 pounds of rotating mass. Also new are Brembo’s monobloc brake calipers replacing the RR’s two-piece binders.

The bike’s Race ABS and traction-control systems are newly optimized for racetrack use, and the ECU now has a launch-control function. The HP4’s rear tire is widened to the 200/55-17 size we first saw on Ducati’s incredible Panigale, and the RR’s optional GSA quickshifter is fitted as standard equipment.

The four-cylinder engine’s class-dominating peak power is unchanged, but a titanium Akropovic exhaust helps give it a welcome boost in midrange output and trims nearly 10 pounds of weight. The HP4 gets cosmetic enhancement with a racy blue-and-white paint scheme, a solo-seat configuration and a tinted windshield. A smaller and lighter 7-aH battery helps make the HP4 the lightest four-cylinder literbike, scaling in at 439 pounds with its fuel tank 90% full.

A World’s First – DDC

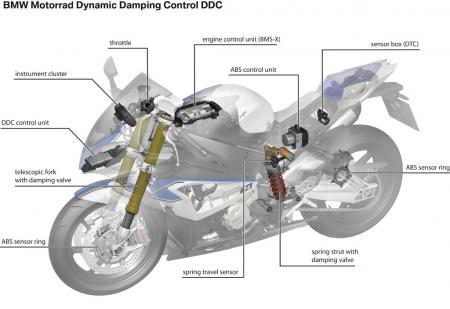

Headlining the upgrades to transform a RR into an HP4 is Dynamic Damping Control, a semi-active suspension system that automatically adjusts damping every 10 milliseconds based on how the bike is being ridden. The DDC’s control unit is mounted in the bike’s nose, and it’s fed data from wheel-speed sensors, throttle position, the shock’s travel position and the traction-control system, including its bank-angle data.

When set to one of the HP4’s street settings, Rain or Sport, DDC delivers a more compliant ride to absorb various road imperfections. Valving becomes tighter in the Race and Slick modes. Within each, the rebound and compression damping settings can be dialed up or down over 15 steps via the handlebar switchgear and updated instrumentation display. Spring preload adjustments require tools.

Because the system is “dynamic,” the electrically actuated suspension valves (first seen on BMW’s 1997 7-Series car) actively change their damping rates based on data pouring into the ECU. So, for example, while the damping is restricted for best control during racetrack use, the computer’s bank-angle sensor can inform the DDC to dial back damping when cornering at a deep lean when forces going through the suspension are less direct.

The right-side tube of the Sachs inverted fork carries the manually adjustable spring, while the left leg contains the damping circuits. Unlike the rear shock, the fork has no provisions for sending suspension-travel data. Optional from BMW is a fork travel sensor that hooks up to a provided input in the DDC computer. This allows for compression- and rebound-damping settings independent of each other.

The DDC performed flawlessly at Jerez, but it’s easy enough to get a good setup on a top-level sportbike for riding on a smooth GP track. DDC’s biggest benefit is likely to be felt on the street. To test the DDC in a street-ish environment, I noted the suspension behavior while riding Jerez’s bumpy pit lane. Then I shut off the ignition and observed harsher damping without the active damping in play.

Although our testing of DDC was limited, it is surely a leap forward, and one that’s only going to get more impressive as it gets further developed. We will definitely be seeing DDC and systems like it on more production bikes in years to come, as the cost of the components likely aren’t very high. When I asked some BMW reps how much the system adds to the cost of the bike, and I threw out a 500 euro value, none of them balked at that price, so the additional hardware probably costs only a few hundred dollars. The system’s greatest cost is the considerable development time needed to finely tune it.

BMW’s On Track

Two items to note: First, how privileged motojournalists are to be caning sportbikes no one else has yet seen in person around a superbly entertaining Grand Prix circuit. And, second, how a production streetbike can make a GP track seem so small!

As is well known by now, BMW’s four-cylinder engine is simply the class of the field, spitting out nearly 180 horses at its back wheel. BMW engineers say the HP4’s powerband has a punchier midrange in the 6000 to 9000-rpm zone, but its peak crank-rated power of 193 PS is unchanged despite the addition of the Ti Akropovic exhaust.

However, more power can be unleashed by replacing the mid-pipe and its catalytic converter, plus removing the muffler’s baffle – both of which disqualify the bike from legal road use. We’re told more than 205 at-the-wheel horses can be produced when fitted with the full exhaust treatment, a race ECU and race gas! (A journalist with deep racing connections told me BMW’s WSB engine is able to make as much as 240 hp for use at high-speed tracks like Monza.) Our test bikes were fitted with the standard Akro exhaust but had their baffles pulled. To my ears, it didn’t sound objectionably louder than S1000’s exhaust.

Honestly, more power was the last thing I was looking for while blasting around Jerez. And despite riding on a GP circuit, I never got out of fourth gear! There is so much power on tap that wheelies are a regular concern on the HP4. Wheelies are attenuated in the first three modes, including the Race setting I initially sampled, but the Slick mode I used for the rest of the day allows for monowheeling antics, aided by “adapted wheelie detection” programming.

Acceleration onto the front straight in second gear is so strong the front end inexorably comes off the ground, necessitating an early shift to third to keep the front wheel from coming up too high and ruining the drive. When I got it right, I saw as much as 155 mph on the speedo before yanking on the brakes for Turn 1.

And the new monobloc Brembos offer spectacular power and superb feedback. The Race ABS package includes new settings in Slick mode developed in the German Superbike championship that seem to completely eliminate intervention on a dry racetrack, allowing rear lift (i.e. stoppies) and rear-tire slides during braking. The non-Slick modes partially link the rear brake with the front lever.

Other brake sets surely have as much power as the HP4’s, but I can’t think of any that work better than these. They’re amazingly powerful with plentiful feedback, and ABS never interfered. I kept off the brakes later and later and never got in too deep. It’s possible the DDC system was keeping the bike stable during deceleration by boosting front compression damping when the shock was nearing its full extension and the throttle was closed. Either way, very impressive.

If the HP4 isn’t quite special enough for you – perhaps you have a Panigale S or an RSV4 Factory – BMW has several options to help set your bike apart.

Competition Package

If you want to enjoy a racer-boy appearance, order up the HP4’s Competition Package directly from the factory. It includes race-designed adjustable footpegs, a carbon fiber tank cover and bellypan, blue wheels (instead of black), and sponsor decals.

Race Kit

Or, if you want to act the part of racer boy and want to take your HP4 into competition, BMW offers several racing accessories, including a sophisticated Software and Calibration kit (about 1100 euro) and a 2D data logger (about 600 euro). The kit features a mind-boggling array of electronic tuning options. In addition to expected fueling and ignition mapping options plus ABS, GSA and pit speed-limiter fine-tuning, the kit also offers customizable settings for engine-brake control, TC and DDC.

More amazing is how most of these settings can be optimized for particular sections of a racetrack, as the ECU is able to know where it is by logging the distance traveled. So, if you need softer damping for a small, bumpy segment of a track, just program the electronic brain to do it automatically while riding that section. Or, if you’d like a little less engine-brake control for first-gear corners, just select exactly how much you’d like on your laptop while you’re in the pits.

I didn’t bother to try the Rain and Sport modes, but we’re told they now provide full power instead of being neutered, with the main differences being lazier throttle response and earlier ABS and traction-control intervention. In Race Mode, I could easily feel TC and wheelie-control intrusion. The Slick setting brings sharper but manageable throttle response and an abundance of optimized TC settings able to be set on the fly: plus 7 to minus 7.

The optimized TC system might now be the industry’s finest. I first tested the neutral “0” TC setting, which I found to be about optimal for the safety margins I usually ride inside. I could feel the rear end moving around under acceleration, but I had no scary moments. Later I tried the “-2” setting, and I shouldn’t have been surprised to encounter a fairly lurid rear slide while exiting Turn 2, a tight right-hander that puts a premium on rear grip while accelerating leaned over.

By early afternoon, the HP4’s Pirelli Supercorsa SPs were getting a bit greasy from all the track thrashing, but we were lucky mid-afternoon to enjoy the additional grip from Pirelli’s new World Superbike-spec 17-inch slick tire that will be used during the 2013 season to replace the series’ 16.5-inchers. We were the only riders outside of Pirelli and the WSB grid to have sampled them.

The extra grip from the race rubber was quite noticeable, especially on corner exits. Where the SPs would regularly be squirming, the slicks hooked up and delivered stronger drives. The 17-inchers surprised many Superbike regulars during a recent test at the Aragon circuit, with several of them posting lap times 1 second quicker than the 16.5s used currently.

And speaking of rolling stock, the HP4’s lightweight forged wheels are the most noticeable upgrade when evaluated from behind the bars. The Fuchs-made wheels deliver much quicker turn-in response and make the HP4 feel smaller than the S1000RR.

Ready For Launch

When heading out for my last session of the day, I stopped on my way out of the pits to test BMW’s new launch-control system. Just come to a stop, hold down the starter button to engage LC – you’ll see an icon lit on the instruments – then pin the throttle. Revs are held at 8000 rpm until you see the green flag – real or imaginary – and all that’s left is to control acceleration via the clutch lever. LC automatically limits torque and inhibits accel-killing wheelies, and it automatically disengages once in third gear or when leaned over for a corner.

For some weird reason, I got a big wheelie during my launch that caused me to back off the throttle, so perhaps the next-gen LC will be better. However, it must be said that no other journo who tested LC got the front end more than a few inches off the ground, so my incident seems to be an anomaly.

During the last session, I began to push my comfort envelope and went faster. I was often seeing the gauges’ green light, indicating faster segment and lap times, and I began to use more TC while enjoying the bike’s sophisticated electronics. Even then, I didn’t once have a scare on the track, a strong testimony to the outright capabilities of this incredible superbike.

The HP4 nears perfection, but there’s always something to be found to bitch about when reviewing motorcycles. For this BMW, its worst behavior was exhibited when exiting Turn 4 while dialing on the power for a fast run down the back straight. There is so much power, even in third gear, that it caused the rear tire to start squirming and cause mild headshake. Not snatch-the-bars-outta-your-hands headshake, but it was a mite disconcerting and noticed by several other journos.

Conclusion

The HP4 truly is a special motorcycle and a technological tour de force. Not only is it an incredibly proficient and potent sporting motorcycle, it also elevates the S1000RR platform to the exotic levels of Ducati and Aprilia – a threshold BMW’s superbike previously had difficulty achieving. The RR’s prestige level has been amplified after taking several victories in World Supers this year, and the HP4 technologically raises the performance bar.

Other than the trifling instability issue we noted at Jerez (and not present on the many other tracks we’ve ridden on with the S1000), the only problem I see with the HP4 is affording it. BMW has yet to set prices for the HP4, but we’re expecting an MSRP at or above 20 grand, slightly undercutting the premium Italian brands. UPDATE: Price details can be seen in this news post.

That’s not cheap, but it seems like a relative bargain for what might be the most capable sportbike ever built. Expect them at dealers this December.

Duke's Duds- Helmet: Bell RS-1 with SOLFX Transitions faceshield

- Leathers: Alpinestars Racing Replica

- Gloves: Alpinestars GP Pro

- Boots: Alpinestars Supertech R

More by Kevin Duke

Comments

Join the conversation