Motorcycle History: Part 2

In the first part of this series, we discussed the multiple paths taken by the self-propelled bicycle through the 1800s on its two-wheeled way to becoming a recognized motorcycle powered by gasoline fed, internal-combustion engines. Here we sample the frantic pace of development as the 19th rumbles into the 20th Century, as engines and chassis benefit from milestone-making innovations.

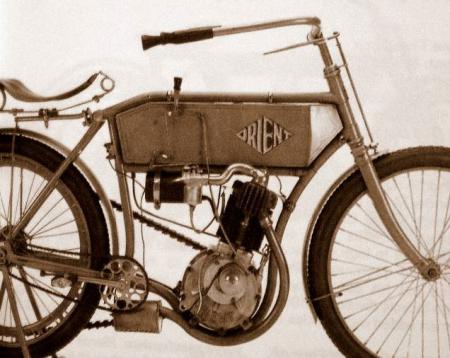

1899 Orient: America’s First Production Motorcycle

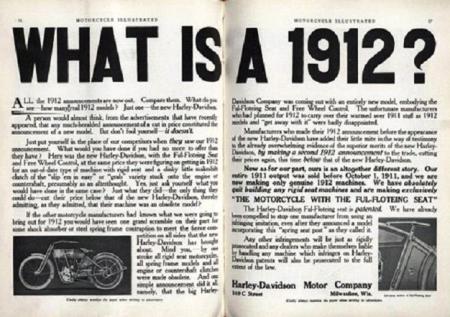

Fans of the original Indian motorcycle often like to remind their Harley buddies that their Springfield splendor preceded production of the Milwaukee marvel by two years; Indian first appeared in 1901, Harley-Davidson in 1903.

But both Indian and Harley were upstaged in the history books (generally unread, it appears), by a Massachusetts bicycle concern called the Waltham Manufacturing Company founded in 1893 by one Charles H. Metz. The name of his machine, and rightful heir to the title “first USA production motorcycle” was the Orient-Aster, better known simply as the Orient. The Aster relates to the machine’s French-built engine, a copy of the ubiquitous DeDion-Bouton.

Its history is traceable back to those so-called “safety bicycles.” One of the early such designs was produced by Charles H. Metz, apparently a rocket scientist on wheels, who conjured up the “Orient” bicycle, apparently a very hot seller.

Motivation for attaching an internal combustion engine to a bicycle came about when Metz wanted a means by which to train his bicycle racing team. Metz constructed a tandem pacer bicycle with the pilot sitting up front, the rear passenger operating the DeDion-Bouton engine housed in the rear section, then put it to work on the Waltham bicycle training track intent of giving his team something to shoot for. The idea worked, the Orient bicycle team gaining victory after victory, which naturally translated to increased bicycle sales for the company. A light bulb went off in Metz’s head.

It occurred to Metz that a self-propelled vehicle, minus the sweat of the brow propulsion, might interest the buying public, and his pacer motorcycle was the bridge between the two worlds. In 1898 he had tinkered up various tricycle and quadracycle versions, eventually focusing on a heavy-duty version of his production bicycle into which he stuffed the Aster/DeDion-Bouton engine. Apparently it wasn’t the best handling contraption, but it moved under its own power, and several prototypes were seen trundling around the Waltham bicycle track.

A big believer in advertising, Metz launched a media blitz of his day and made history when his 1899 catalog listed his pace machines as “Orient Motor-cycles” apparently the first published catalog usage of the term motorcycle. Previously the ads and literature of the day had referred to them as motor-bicycles, so Metz can also be one of several credited with officially coining the name “motorcycle.”

The official public debut took place on July 31, 1900 when Metz launched his invention at the Charles River Race Park in Boston which also happened to be the occasion for the first officially recorded motorcycle speed contest in the United States. The Orient won.

About a year later, in May 1901, the Orient appeared in the winner’s circle again, this time venturing to the first West Coast bike race which took place at a one-mile Los Angeles horse track. The factory rider was Ralph Hamlin who pied-pipered three other riders across the finish line, the 10-lap race completed in 18.5 minutes which factors out to be about 32 mph. The Orient would go on to establish the American record for the mile at one minute and ten seconds. As a result of these much publicized successes, Orients were soon being piloted around by adventuresome riders in many major U.S. cities.

So confident was Metz in his new motorcycle that he said good-bye to the Waltham Co. and opened his own business behind the Woolworth store at Whitney Ave. and Moody St. He was going to build his own motorcycles.

Sticker Shock Circa 1902: $250

The Orient motorcycle was relatively expensive at an MSRP of $250, quite a lump sum more than a century ago. What you got was a 2-hp gasoline engine that carried about five quarts of fuel, good enough to take you 100 miles, again a fair piece at the turn of the century, especially considering the quality of the roads.

About four years later, Metz introduced a two-cylinder version that doubled the horsepower of the Single to 4.0. At this point Metz teamed up with the Marsh Co. of Brockton, MA, the merger producing the high quality Marsh-Metz motorcycle appearing in 1908.

The Marsh Brothers, W.T. and A.R., had first built their 1-hp single-cylinder bike in 1899 as the Marsh Motor Bicycle. By 1902 they had built a 6-hp belt-drive racer that could reach 60 mph.

After the merger to form the American Motor Company, the motorcycles bore the name Marsh & Metz or M.M. and would mark another milestone when it produced the first 90-degree V-Twin in the U.S. Marsh and Metz also sold engines to other builders such as Peerless, Arrow and Haverford, but by 1913 the company was no more, Charles Metz switching gears to automobiles.

1903 - First U.S. Transcontinental Bike Ride

The short-lived “California” was built by The California Motor Company of San Francisco. It was founded in 1901 and made history in both the short run and the long run.

In 1903 a benchmark in motorcycling history was accomplished aboard a 90cc California piloted by an intrepid fellow by the name George Wyman when he became the first motorcyclist to make a transcontinental trip across America. Make that the first ever to make the trip by means of any kind of motorized vehicle.

Starting in San Francisco, he traveled over 3800 miles on his spindly 1.25-hp machine over non-existent roads. He arrived at New York City 50 days later, missing 1903’s Fourth of July by just two days. His hands were wrapped in bandages and he had to pedal the motorcycle the final 150 miles! Newspapers and magazines of the day gave extensive coverage to the event, putting the name of the company, George and the state of California in the public’s eye.

The California eventually morphed into the Yale motorcycle after the original company was bought by the Consolidate Manufacturing Co. of Toledo. The first Yale-badged bikes appeared in 1909, by then having grown to 3.5 hp.

Considered a gentleman’s machine, with a stalwart reputation for reliability, the Yale came appointed in elegant gray accentuated by polished nickel hardware. Fuel is carried in the distinctive cylinder slung under the top frame member, while the large canister set astride the handlebar contained acetylene for powering the headlamp designed to light the way on a dark night’s ride. Starting was via pedaling with the rear wheel up on its centerstand, while belt-drive propelled the bike. The “4P”emblazoned on the gas tank along with the Yale logo stood for the rated horsepower, sufficient for a well-mannered 45 mph.

The Yale became of the more successful of the early independent motorcycle manufacturers, the main factor being that the company was better capitalized than most other bike builders of the day. As a result they were able continue with their single-cylinder machines and also develop a V-Twin model. The company was in production until 1915 when it switched to building more profitable products for WWI.

1905 – Some 28,000 motorcycles are officially registered in England. Motorcycle sales are starting to boom, although several busts fell among the hundreds of motorcycle companies that came and went. 1905 also saw the debut of the world’s first V-Twin, the 2300cc Czech-designed Laurin & Klement CCR.

1907 – The Fastest Man in the World: Glenn H. Curtiss

“Bullets are the only rivals of Glenn H. Curtiss of Hammondsport." - 1907 newspaper headline

On January 24, 1907, Glenn Curtiss roared across Ormond Beach on the east coast of Florida at 136.3 mph to set a land-speed record that would stand for 11 years – and then only surpassed by an automobile. It would not be until 1930 that a motorcycle would best his feat of daring-do and mechanical design.

Curtiss is a true American hero and a larger-than-life personality whose exploits would even inspire a popular series of youth books "The Adventures of Tom Swift" penned by Victor Appleton. And yes, there was one volume circa 1910 titled “Tom Swift and His Motor-Cycle or Fun and Adventures on the Road.”

Curtiss was always looking for new adventures on or off the road, whether in cars, boats or airplanes. Back in 1907, the 29-year old Curtiss had already invented or developed many of the more than 500 designs and components he would conjure up during his lifetime, including a hand in the development of the Wright Brothers first airplane and additional aeronautical experiments in partnership with Alexander Graham Bell that included developing and patenting the aircraft aileron now universally intrinsic to controlled flight.

Whether it was propeller-powered or rolled on wheels, Curtiss was always pushing the envelope. While his lasting fame would rest with aircraft, it all began with motorcycles. As a result of his experience as a bicycle racer, Western Union bicycle messenger and bicycle shop owner Curtiss became interested in motorcycles. In 1901 he began motorizing bicycles with his own single-cylinder internal combustion engines, initially fashioned from tomato cans.

He not only talked the talk, he walked the walk, racing what he built and earning the accolade in 1903 as the “First American Motorcycle Champion” by reaching 54.6 mph. By 1905, he set the world speed records for one-, two- and three-mile events. Besides piloting his speedsters, he also tinkered out a number of advancements, including the handlebar twistgrip throttle control.

His new record-breaking bike came into existence due to the ever increasing demand for more powerful aircraft engines for the burgeoning production of early 20th-century flying machines. The bike was basically a rolling, but not quite flying, test bed for the new Curtiss 40-hp “monster” motor.

The configuration was based on a very square 3.25 x 3.25 inch bore and stroke that displaced a potent 269 cubic inches. While his preceding engines were primarily single cylinder and 50-degree V-Twins, Curtis went to a 90-degree design featuring cast-iron F-type heads as utilized on his smaller displacement powerplants. Moreover, it dispensed with head gaskets thanks to the quality of its design and manufacture. Inside the massive hunk of metal lurked a solid billet steel crank, while internal lubrication was handled via a dry sump and random splash system.

Under the valve covers, inlet valves were activated by atmospheric pressure while pushrods actuated the exhaust valves. Fed by twin carbs, also Curtiss designs, the throttle cables were hidden inside the handlebars. The electrical system relied upon jump-spark ignition energized by dry-cell batteries.

While it looked ungainly with its 4000cc engine suspended in what was a heavily beefed up bicycle frame with a 64-inch wheelbase, the overall design benefited from a power to weight ratio (one hp per 6.8 pounds) that was advanced by any standard, especially by those of 1907. The bike supposedly tipped the scales at merely 275 lbs.

The four-mile course at Ormond Beach was divided into a two-mile section for reaching top speed, a third mile for timing purposes, and last but not least, a “slow down and stop” mile. As the bike was shaft-driven with no clutch and but one tall gear, it was an all or nothing proposition. One kept twisting the throttle and let the speed build while the screaming unmuffled pipes scattered sea birds for miles. As the Curtiss Museum director comments, “It must have sounded like the Wrath of God!”

Curtis was clocked at 136.3 mph in the timed section of the course. He would be the first man to travel one mile in 25.25 seconds, a feat of mechanical design and personal courage that earned him the title of the fastest man on earth.

Armchair pundits of the day reportedly snorted with disbelief, espousing their firm belief that is was a hoax or fable since no mortal man could breathe at the reported speed. It would be the V8’s one and only day in the sun, the only time Glenn Curtiss would take it up to speed. But once was enough.

If you want to see the real McCoy, you’ll find it at the new Smithsonian Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center located adjacent to the Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, VA ( http://www.nasm.si.edu/).

1908 Indian “Camelback”

The year 1908 was a time of prodigious American achievements that would reshape the world. Henry Ford rolled out the first Model T, aka the “Tin Lizzy,” opening the door and roadways to millions with an affordable automobile. In the same year his competition, a company called General Motors, was also founded. But whether four wheels or two, the roads traveled by either car or motorcycle were an endurance challenge for machine and passengers.

The Indian Motorcycle Co. of Springfield, Massachusetts, endeavored to smooth out the rough ride with a cartridge-spring front fork for its 213cc single-cylinder-powered machine. Another major improvement over previous models included twist grips that could now control both the throttle and the spark advance/retard, which made controlling the machine all the easier, something appreciated by the rider on a machine that could accelerate to a then heady 35 mph, or perhaps even 45 mph as company ads proclaimed.

Design technology was also catching up, as this was the last year the Indian would sport its distinctive gas/oil tank from which was derived the moniker “Camelback.” Early motorcycle manufacturers had for several years experimented with various attachment points for the fuel reservoirs to what were for the most par beefed up bicycle frames, with Indian choosing the rear fender mounting position.

And speaking of frames, that long thick tube riding parallel to the front down-tube served as a container for several dry-cell batteries, while the shorter, rocket-shaped tube contained the Indian’s ignition coil. The 1908 also benefited from the adoption by Indian of the German-made Bosch magneto that resolved a previous problem caused by the poor quality of the dry-cell batteries.

The bike’s overall design, considered state of the art at the time, was based on one conceived in 1901 by the venerated engineer Oscar Hedstrom and brought to fruition when he teamed up with keen-eyed businessman George M. Hendee. Thus the name Hendee Mfg. Co. is emblazoned in gold on the Camelback tank. Hendee, an accomplished cycle racer and builder of the Silver King bicycle, wasn’t happy with the motorized pace bicycles of the time and thought he found the right ticket when he met Hedstrom in1900 at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Hedstrom’s design included a chain drive, while others still relied on belt-drive systems. By 1903 the Indian motorcycle was known internationally in part due to its reliability and two significant features: the inclusion of a transmission and a single cable-controlled carburetor which made riding the Indian a much simpler affair than other machines of the day. The company sold 1181 motorcycles in 1905, a significant sales success.

Five Indian models, both Singles and Twins, were offered to the public in 1908. It is estimated that only 20 of the first edition of the Camelback still exist today.

1910 – More than 86,414 British bike riders have registered their machines. By this year 31 U.S. motorcycle companies are in still in production, although several have fallen by the wayside

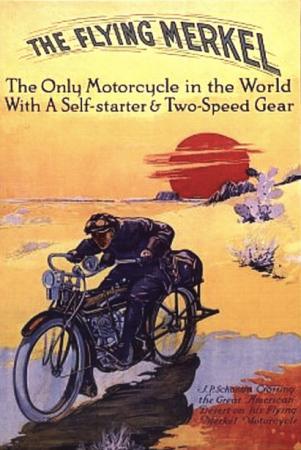

The Flying Merkel

In 1911, the U.S.-built Flying Merkel came in both race and street trim. The touring version was one of the first motorcycles to employ suspension beyond just seat springs and rubber tires. A monoshock system mounted beneath the seat supported the rear wheel, while twin springs suspended the front fork.

The advanced suspension design reportedly produced the addition of "Flying” term to the Merkel name, while others say it was its speed and performance that left its competitors literally in the dust.

1911 Pierce - The Four-Cylinder Luxury Motorcycle

Pierce had become in 1909 the first American motorcycle offering a four-cylinder engine. The company was at the leading edge in all things with wheels, including bicycles, cars and motorcycles. The company’s guiding force, George N. Pierce, started all the wheels rolling as the founder of both the Great Arrow Motor Car Company and the Pierce Cycle Company, both enterprises located in Buffalo, New York. Pierce-Arrow automobiles were the acknowledged “prestige cars” circa 1901-38.

But it was George’s son, Percy, who steered the company toward motorcycles after he was given charge of the company’s bicycle activities in 1908. It seems that Percy had a been bitten by the bike bug after a trip overseas to Belgium where he encountered the now famous FN four-cylinder machine designed by Paul Kelecom. So impressed, in fact, that Percy purchased one and brought it home to Buffalo and went on to develop the Pierce line of fine motorcycles in keeping with the reputation for fine motor cars.

The introduction of the Pierce Four engine design in 1909 literally astounded the American motorcyclist of the day, as it was that much of a “quantum” leap over the standard single- and twin-cylinder fare available.

While the Pierce did appear to be a clone of the Belgian FN, it differed from the FN’s Intake-Over-Exhaust design in several ways. Instead of using a side-valve arrangement with intake valves on one side of the engine and exhaust found on other, the Pierce used a two-cam system that took on the name “T-head.”

The 696cc engine was used as a stressed member of the chassis, and its four cylinders and 7 horsepower could vault it to a heady 55 mph. Its shaft-driven rear wheel was the first such final-drive application in an American motorcycle. Early models were direct drive, but by 1910 it was available with a clutch and two-speed transmission.

The sophisticated lines of the elegantly designed machine can be attributed to the 3.5 inch diameter, 18-gauge steel frame tubes that were internally copper plated. The upper and rear frame tubes could hold seven quarts of fuel while the front downtube carried five pints of oil.

The Pierce, later available with a 592cc single-cylinder engine, was described as “The Vibrationless Motorcycle,” with exports to 14 different countries. But the expensive-to-produce machines weren’t profitably to build, and by 1913, Pierce ceased its motorcycle operations.

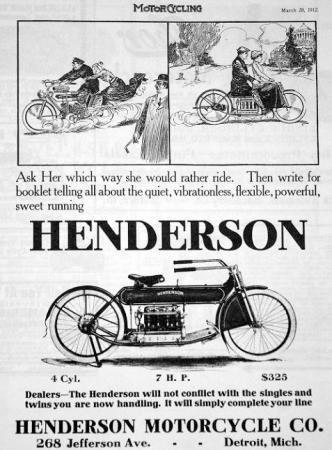

1912 Henderson Four Cylinder – Elegance in Motion or at Rest

Detroit-based Tom and William Henderson had started building their four-cylinder machines in 1912. Four individually cast cylinders were mated to an aluminum crankcase on three main bearings, producing a purported 7 horsepower via 965cc and good for a claimed 55-mph top speed in 1913. It was uprated in 1914 to 1065cc and 8 hp.

Instead of pedal start, standard for the day, the design employed a car-style crankshaft, the very nature of the inline-Four imparting an automotive aura to the long wheel-based machine that exuded elegance, refinement and grace of movement. It offered the rider the smooth transmission of power, fine handling and easily controllable operation. It would establish a benchmark for others to follow.

From 1912-1916 the Henderson Four round tank, long wheelbase was produced in a variety of configurations, but the 1912 and 1913 garner the most favor. While the early machines are single speed and do not have transmissions, they did feature a small clutch on the motor sprocket chain drive. A two-speed transmission became available in 1914. Other features included a rear band brake, rear-mounted tool box, dual brake pedals and interesting footboards.

In a not so hostile takeover, bicycle mogul Ignaz Schwinn acquired the vaunted Excelsior company in 1911 and then in 1917 acquired another "trophy" company in the form of the Henderson Motorcycle Co., purveyors of the now iconic Henderson Four seen here.

It is estimated that less than half a dozen 1913 Henderson Fours have appeared worldwide over the past two decades.

1913 – Bike registrations in England have jumped to 180,000, adding nearly 100,000 riders over the previous three years.

1914 – Cyclone Whips Up on the Competition

For a brief but brilliant moment, the American-made Cyclone was in the spotlight, its prowess earning it praise as “the most feared competition machine of the era.”

Its first appearance took place in early 1914 at a California dirt tracks facing off against the top dogs of the day, Harleys and the new Indian 8-valve racer that was also making its first showing at the tracks. When the checkered flag fell, it had vanquished all that came up against, reaching speeds of 105 mph. It even set a record when racing and winning against the reigning King of Speed, Barney Oldfield driving his then-famous 300-hp racecar.

Just as suddenly as its star had risen, the Cyclone faded from the race tracks, the company falling into financial hard times and folding altogether in 1915. Cyclones in private hands continued to appear in events for several years, as late as 1922, Cyclone motorcycles were banned from many competitions because “they were too fast for the tracks.” Or too fast for the other manufacturers still in the business of selling motorcycles to the public?

The War Years

On a sunny Sunday, June 28, 1914, two pistol shots fired in the streets of Sarajevo, Bosnia by a 19-year old would change the world forever. Empires would fall away and The Machine Age would catapult warfare into a catastrophic new dimension as Europe and eventually the U.S. would be embroiled in the “War to End All Wars.” This was an international upheaval that would dramatically affect the world's motorcycle industry, as civilian production was diverted to the demands of the military on all fronts, but which would eventually “trickle” down in the post-war years to benefit the consumer, both on the street and on the track.

Related Reading

Motorcycle History: Part 1

More by G.P. Garson

Comments

Join the conversation