Higdon in South America: Part Next

If you were wondering what had happened to our intrepid South American correspondent, you weren’t alone. After hearing of the problem with his right eye reoccurring in the sixth installment on February 20, I feared the worst – that Bob had caught a flight back to the US and his trip had come to a disappointing end. My emails to him went unanswered. Then, last night as I was checking for something else in my Junk file, guess what? How does that work, you’ve been corresponding with a person for years, and all of a sudden gmail decides they are Junk? Anyway, with no further ado, Part VII.

February 21, 2018

Tiwanaku ruins, Bolivia

Yesterday I became carry-on luggage. I am now a passenger in the chase van operated by Jairo (pronounced HIGH-row) Ruíz, a resident of Bogotá, Colombia, who will follow us to the bottom of the continent. From there the tour group members will fly home, arriving in a matter of hours. Jairo’s return journey will take three weeks. To the rest of our crew he is a rarely seen lifeline; to me he is the reason I remain on this venture at all, even as an animated suitcase.

Following a course from A to B each day has been a different experience for me on this ride, even though I was an early adopter of global positioning satellite (GPS) receivers. The earliest models simply gave you a straight-line calculation from one data point to another; it was up to you to figure out the turns. Then auto-routing followed, in a form much like everyone uses today. Plug in an unknown address and just follow the yellow brick road to your destination. Easy peasy.

That’s not the system we’re using, mainly because GPS devices can be personalized (don’t make U-turns, avoid dirt roads or tolls, and so on). Instead, Helge Pedersen five years ago created a trail of bread crumbs for every foot of this ride from Cartagena to Ushuaia. As opposed to auto-routing, which can produce different routes depending upon the GPS’ internal settings, this system is called tracking. If you, like Hansel and Gretel, follow the bread crumb trail, usually denominated as a green line on the GPS map, theoretically you cannot go wrong.

You see where this is headed, right? Jairo dutifully dropped the day’s destination into the GPS, stuck the unit into tracking mode, and followed the green line out of Cusco into a mud-slimed construction zone that brought half the bikes in the field to their knees in despair. Eventually everyone was able to redirect onto the correct route (mainly by using the disapproved auto-routing), but it was no way to begin the day. It was our grim luck the bread crumb trail had been horrifically overtaken by highway remodeling. This trip is advertised as, and delivers as, adventure touring: You do what you can to overcome. The entire route is a no-whining zone.

Once out of Cusco, however, we climbed into the majestic valleys of the Andes. It was everything that Colombia and Ecuador had offered but reaching twice as high into the clouds. I was looking forward to proving my thesis that living in such rarefied conditions retards the growth of animals that depend upon oxygen. I am certain, for example, that the Bolivian adult male has a mean height of 31 inches and lungs the approximate size of weather balloons. I also read on the internet that if you raised llamas at sea level, they would grow to 18 feet at the shoulder on average. Incidentally, I ate llama at dinner tonight. It tastes nothing like chicken.

Jairo had popped a USB stick of oldies into the dash and was running the tracks through the van’s radio. I think he may have done this for my sake, but in truth there is no gringo with a greater love of Hispanic bubble gum music – basically a mildly advanced form of doo-wop in Spanish – than I. I glanced up at the GPS, centered below the rear-view mirror on the windshield. We were closing in on 3,500 meters, roughly 11,500 feet. I mentioned it to Jairo: “Tres mil quinientos metros.” The default language in the van is Spanglish. Neither of us can speak enough of the others’ mother tongue to make conversation either meaningful or painless, conditions that produce long periods of silencio.

He replied that we’d be at 3,800 meters at the end of the day. I shook my head. My entire life has been spent within 300′ of sea level. I shouldn’t be up here in this alien land. Taking 15 steps at 12,000′ simply punches 1″ holes in my already perforated lungs, my tiny, atrophied lungs, not those big ass bags the Bolivians have.

The radio rolled on:

But I don’t know how to leave you

And I’ll never let you fall

And I don’t know how you do it

Making love out of nothing at all.

Ah, another of the incomparable Jim Steinman’s masterpieces. And who to deliver it but Air Supply? I turned to Jairo and smiled.

“No hay Air Supply aquí.” There’s no Air Supply up here.

“Nunca.” Never.

More by Robert Higdon

Comments

Join the conversation

Great series, just read them all, and curious to see if the eye condition cleared up and you made it to Ushiaia. Following Tim Burke on Instagram, who just got there from the US on an R1200GS, and is now heading up Argentina and into Brazil. Bucket List!

Good piece; glad to see the ball is still rolling south.

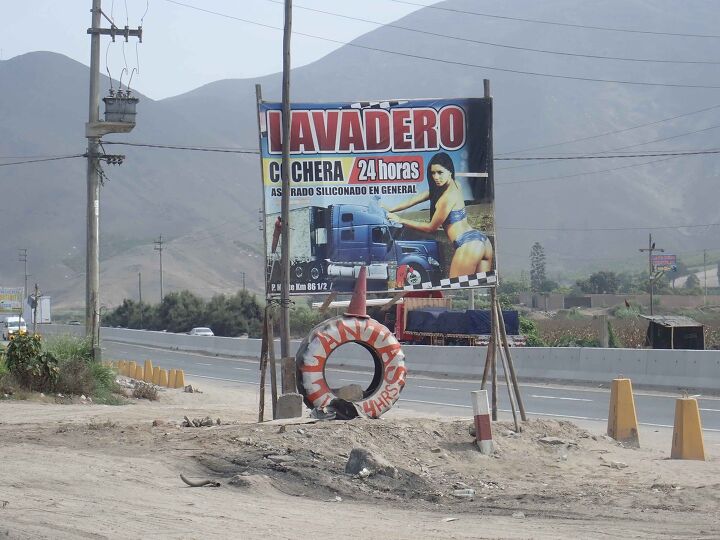

That scenery in the 'lavadero' photo looks just like a scene from the SoCal high desert, except raised about 8000 feet. I'd like to hear how the bikes are performing at that altitude. Even with EFI power is lost and who knows what else could be affected. Any modifications to cope? Also, how's the eye(s)? Physical issues from climate and altitude are useful to know for anyone planning such a trip. Maybe next report?