Head Shake - The Long Haul

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost

There comes a point where you just do not feel like stopping, where getting off the bike feels unnatural. It doesn’t start that way, it ends that way. Presumably you probably have a destination you want to get to: your own bed, your own coffee maker, your spouse, your front porch. Interstates are great for that, and I detest them. They are heartless, soulless slabs of asphalt and concrete looking at the same thing over and over again: orange barrels, the usual fast-food slop chutes, and truckers and tourists. That’s not living.

And that’s not what you are doing. You want to get to that place where you simply keep going. Where that is the most natural thing. Weather, missing loved ones, wanting to sleep in your own bed and not digging clothes out of a saddlebag; none of that matters. You just want to roll. That feels natural, being stationary does not. The only natural thing is to be making asphalt disappear behind you. You need U.S. and state highways for that, and along the way you get to meet the people you are traveling through. That is a remarkably free feeling.

I establish habits. I am a creature of habit.

Wake up early before sun break, drink some coffee and be ready to ride at dawn. It is solitude; you have thousands of miles with yourself to yourself, and flying solo with nothing to answer for except getting done what needs to be done. On the east coast you may mark progress by the odometer, stop every 100 miles and fuel up. Out west is different; you mark progress by states, and you get fuel where you can. And pretty soon, like some weird form of moto-meditation, it sets in. The road, you, the bike, the journey; that’s you.

You think about too much, or you think about too little; the road will help you figure that out.

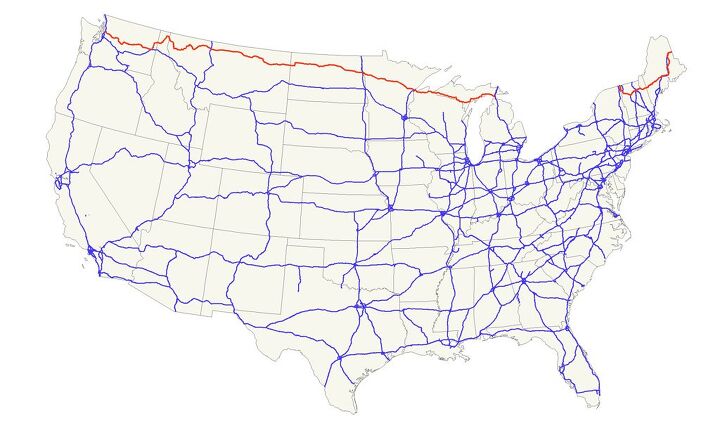

It is 2,100 miles from Kalispell, Montana, to Sunbury, Ohio, going the way I chose anyway. And for a good part of that we can fly. Mind your manners in town, but out on the road you can wick it up. It’s a remarkably civilized way to travel. You don’t stare at a speedo, or the instrument pod, you scan the horizon and the road as you should be. It works.

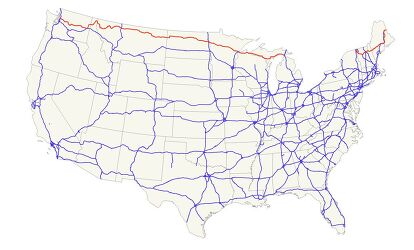

And the route I chose was US Route 2. It is our farthest north highway, if you can call two lanes a highway in our country, and you can alter time and space with the throttle as you see fit. You can also look for gas stops because they matter out there. Mind your manners in town and observe speed limits but otherwise just go. Every night demands a T-bone steak, a baked potato, and a beer, at least in my world. Fries are okay.

You need to go to foreign places, places you are not used to. Surround yourself with different things and people. My intention was to dispense with Montana, North Dakota, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the upper peninsula of Michigan before being compelled to turn a wheel on an interstate at the Mackinac Bridge. The payoff is obscure roadside attractions, old kitschy hotels from another era, and people not used to the normal onslaught of humanity interstates bring. These were roads built in a simpler time which is fine by my simple state of mind.

In a way, this manner of travel most mimics life, you elect a direction to go and have some vague guidelines to follow, but as to what challenges you encounter, what people you meet, and what you see, there’s just no way of knowing. You just let it unfold, adjust on the fly, be surprised at times, and in doing so grow.

A beautiful girl in a desolate Montana gas stop on the high plains; the Fort Peck Indian Reservation; hanging with the Sioux on the res; a walleye fry and shotgun raffle; a Richard Bong roadside memorial; the geographic center of North America; miles and miles of sunflower fields as far as the eye can see; the slate gray water of Lake Superior and the deep blue of Lake Michigan; a giant plastic lumberjack; and the unerring pulse of a big Boxer Twin that just wants to run. These things are what happens when you get off the interstate.

It’s all out there, and the peace that comes from backroads travel through areas time and the interstates forgot. But the closer you get to home, all the people you have met and the things you have seen that have changed daily, the constant motion every day that seemed like such a task at the beginning, it now feels second nature. Heading down US 23 in Ohio on a glide path for home, I wondered, dreamed really, “What if I just kept going, woke up in a new place every day, met new people, saw new things?”

That could not happen of course. I had responsibilities at work and people that loved me at home, but it felt so right to a part of me, anyway. But to capture that feeling for even a short period of time, from skating over ice patches on the front range of the Rockies, to hailstorms in North Dakota, to sweating through Ohio cornfields with every vent open on my Aerostich Darien jacket. To compress that much living into such a short period of time is irreplaceable. And a motorcycle is the perfect vehicle, the only machine in my opinion, which opens the world up that way.

Ride hard, travel light, wear layers, and look where you want to go.

About the Author: Chris Kallfelz is an orphaned Irish Catholic German Jew from a broken home with distinctly Buddhist tendencies. He hasn’t got the sense God gave seafood. Nice women seem to like him on occasion, for which he is eternally thankful, and he wrecks cars, badly, which is why bikes make sense. He doesn’t wreck bikes, unless they are on a track in closed course competition, and then all bets are off. He can hold a reasonable dinner conversation, eats with his mouth closed, and quotes Blaise Pascal when he’s not trying to high-side something for a five-dollar trophy. He’s been educated everywhere, and can ride bikes, commercial airliners and main battle tanks.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

"You pile up enough tomorrows, and you'll find you are left with nothing but a lot of empty yesterdays. I don't know about you, but I'd like to make today worth remembering." - Harold Hill

This is so inspiring. I hope to take a trip such as this one day soon.