Head Shake - Rain Dancers

.and the nine lives of Nelson Ledges

Nelson Ledges Road Course in the wet was stickier than Summit Point Raceway in the dry. This was one of the first of many epiphanies I had in 1986 in my first full season of racing with WERA. I had shed my international orange “I am a Hazard” t-shirt along with my provisional novice status the year before with crash-free races at Pocono and Summit Point, and I was now a full-fledged novice racer free to crash with impunity so far as my license status was concerned. An option I would avail myself of at first opportunity.

The season had barely begun the next year and I wasted no time going out on that chilly April morning and crashing in the first practice at Summit Point, a low-side get-off out of Turn 5 on the gas. I wanted to leave no stone unturned in my early racing education.

This led to one of my other early epiphanies; Summit is slippery and it’s best to ensure that you have stopped sliding before trying to get back on your feet to pick up your bike. It stands to reason that a bike on its side throwing sparks is probably still sliding; chances are good you are, too. Man cannot run 40 miles per hour, and I eventually resolved to stop looking silly trying. I faced something of a steep learning curve early on, but I dutifully applied myself and took notes. My throttle control improved.

Tracks have personalities; you develop a relationship with each one. Some are friendly and treat you kindly, others are malevolent. Atany given track you may meet a lifelong friend. Or you may, through trial and tribulation, forge the love of your life.Or a track may hurt you or your cohorts. Tracks are fun and capricious and deadly serious, sometimes all three in one day. More often the former than the latter, thank goodness. In other words, tracks are a lot like life, with more immediacy.

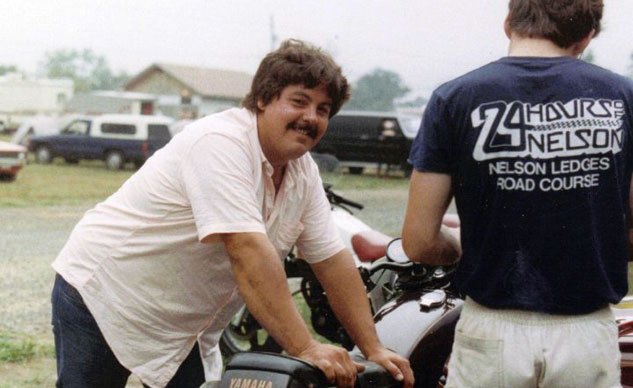

Some tracks have a reputation that precedes them. Nelson Ledges was one of those road courses due in large part I suspect to its 24-hour endurance event. Everybody who pulled on a set of leathers and turned a wheel in anger – or at least in grim determination – in North America knew of the 24 Hours of Nelson Ledges and its western equivalent, the 24 Hours of Willow Springs, and spoke of them with a certain amount of respect. What they didn’t know about Nelson in many cases was the rudimentary nature of the facility, the prevalence of rain in northeastern Ohio, and how bumpy the track was.

Summit Point in the dry back then could teach you how to win at Nelson Ledges in the wet simply because in the ’80s you would slide at Summit rain or shine, hot or cold. “Slippery” Point, as some folks called it, was an outstanding place to learn the finer points of sensing traction. If you were carrying the kind of speed you needed to win at Summit, the bike would move around, the rear would step out, the front end might push, both ends may hook and slide, hook and slide, and the early concrete patches might as well have been ice. The track surface was ever changing both seasonally and annually, you never stopped learning the surface of Summit in those early days.

It was important to stay loose going out for a race at Summit back then. I got in the habit of flapping my arms up and down on the bars rolling up the hot pit to ensure I was not tensing up on the controls. The aim was to keep inputs to a minimum on the bars: they were for braking, turning, and accelerating, not doing chin-ups on. Standing up on the pegs rolling in the paddock, bouncing on the pegs, keeping the hips loose, this was all a ritual in preparation for letting that bike move around where it wanted to in the corners. The idea was to work with the bike and feel what it was doing, not fight it. This education at Summit in the dry would pay dividends at Nelson in the wet.

Nelson was very hard on equipment and racers. I called it a paved motocross track more than once over the years. Oddly, the faster you went, the better the bumps got, or maybe it was just the track playing with perceptions as it became more difficult to discern the grass growing through the generations of asphalt patches at speed. The exit out of the carousel onto the back straight was comprised of whoops that were quite happy to punish cush-drives, transmissions or really expensive wheels that were designed for billiard table-smooth track surfaces, to the point of failure.

A visitor to Nelson Ledges couldn’t help but take notice of two distinguishing characteristics; the track had an abundance of traction and latrines that would gag a maggot. Now, granted, you may have a table-top jump at the apex of Turn 1, or what oddly appears to be a hole because it is a hole at the apex of the kink on the back straight, and you may even be pogo-ing out of the carousel on the gas, but the one thing you had going for you at Nelson was that cheese-grater surface with the kind of gription normally associated with southern seashell-laden tarmac. The kind of tire-shredding, heat-generating grip that turns tires blue, and in the wet Nelson was sticky – stickier than Summit in the dry on most days.

As a result, if you had learned your lessons at Summit Point about the folly of thinking you actually control every physical law in the galaxy, if you had checked your tire pressures and set up your suspension as best you could, if you flapped your arms like a goose heading up pit lane, and if the skies opened up as they often do in northeastern Ohio, you were well poised to podium and maybe even win. The first rule of winning in the wet is surviving to see the checkers, which brings us to the war of attrition aspect of the whole ordeal.

Rain on a race track can discombobulate people. After all, most people have been cautioned their entire lives, “Slippery When Wet.” The state sees a highway overpass it feels compelled to put up a sign telling you just how slippery wet can be. That’s fine, but when your home track is “Slippery When Dry,” only a few minor mental adjustments are needed to account for the peculiarities of a wet track, mostly having to do with the other riders, and you are in your natural environment. You like slippery! You excel on slippery!

The rules of rain racing are really quite simple: You want to finish and you want to take the checkers in front of the other racers. Rain takes away traction to a degree, but so does Summit Point on a good day. However, rain and the ensuing roostertails kicked up by the bikes take away visibility. Passing becomes more problematic so a good start is essential. If you can get out front, you have a huge advantage in that your ability to see where you are going is far better than anyone behind you and you can pick your line accordingly while those chasing you eat precious seconds racing by Braille just to keep your tailsection in sight. Rocket the start and you are well on your way to a good day.

Second, smooth riding is rewarded and the ham-fisted are penalized. Crashing primarily occurs in one of two areas: the entry to turns or the exit of turns. In all instances you should always position yourself to the inside of any possible pass you anticipate making. Don’t be a bowling pin.

Rain crashes can be strange affairs, almost graceful in a way the laws of gravity appear to be suddenly suspended and the rider and bike ahead of you go down in a splash trailing their separate plumes of water to the outside of the corner. You, of course, are on the inside, unmolested, looking through the corner, not at the water follies accompanying all that scraping metal noise. You have just picked up another place. Continue doing this until you see the checkered flag. Do it well enough and you win.

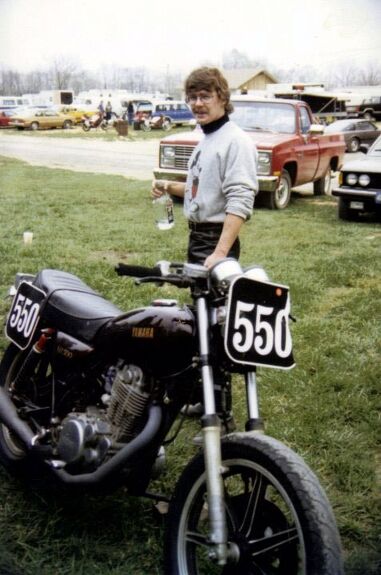

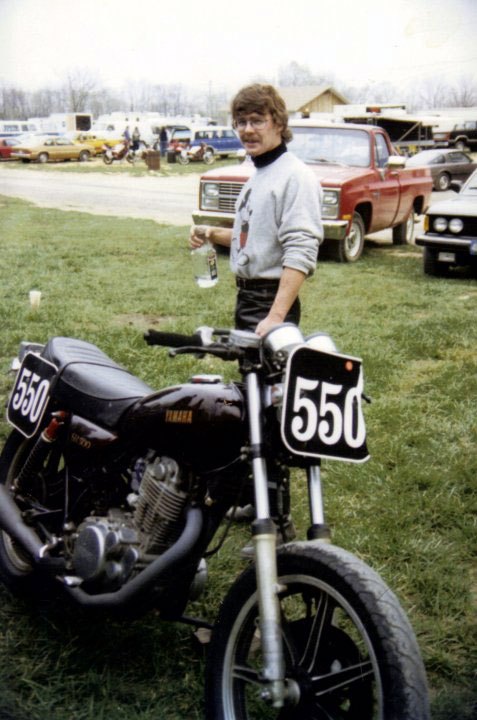

Wet is the great equalizer, and horsepower advantages are often negated. I won my first race in the rain at Nelson Ledges on a bike that was nowhere near the fastest on the track that day or any other. Underdog wins under adverse conditions are the kind of things that keep novice racers going when the money is tight: You just got off work, you still need to load the truck, and registration and tech will open promptly at 0700 tomorrow morning 550 miles away. The only people that would engage in such irrational behavior are the daft and the dreamers, the knee draggers and the rain dancers.

I think about all this right now as I watch summer slow down to its August crawl. This is the time of year when those racing for regional and national championships will be looking at remaining events and counting points, as well as the dollars remaining in their checking accounts. They will think about those tracks remaining on the schedule. They will not be thinking of Nelson Ledges, not this season at least.

Nelson Ledges, the deceptively fast little race track that could, with its storied history and formerly fetid latrines, no longer holds motorcycle races. Hemmed in by insurance requirements and fiscal concerns, the stewards of the track endeavor to keep the gates open in hopes of returning the facility to its former glory. They maintain a Facebook page that they update from time to time.

At the end of the day the viability of any race track, or a racing endeavor, is directly proportional to the dreams it spawns in both owners and competitors alike. Decades of chasing those dreams build the histories, each one unique and irreplaceable, endemic to all the great tracks. To some, when they hear Nelson Ledges, they hear much more than just a place in northeastern Ohio; they hear the howl of an inline-Four through the kink at night and think of hallowed ground from the 24 Hours days and the countless endurance and sprint races gone by. They may even think of those god-awful latrines with a fond chuckle.

Racers grow old and retire, and racetracks too often become shopping malls or housing developments. But it still rains in northeastern Ohio, there are still people dedicated to restoring Nelson Ledges to its former glory, and I suspect that when the last engine shuts down for the day, the groundhogs still come out and sun themselves on the back straight, never too far from their holes.

Ride hard, remember to wave to the corner workers on your cool down lap, and race to the checkers.

About the Author: Chris Kallfelz is an orphaned Irish Catholic German Jew from a broken home with distinctly Buddhist tendencies. He hasn’t got the sense God gave seafood. Nice women seem to like him on occasion, for which he is eternally thankful, and he wrecks cars, badly, which is why bikes make sense. He doesn’t wreck bikes, unless they are on a track in closed course competition, and then all bets are off. He can hold a reasonable dinner conversation, eats with his mouth closed, and quotes Blaise Pascal when he’s not trying to high-side something for a five-dollar trophy. He’s been educated everywhere, and can ride bikes, commercial airliners and main battle tanks.

More by Chris Kallfelz

Comments

Join the conversation

"You just got off work, you still need to load the truck, and

registration and tech will open promptly at 0700 tomorrow morning 550

miles away. The only people that would engage in such irrational

behavior are the daft and the dreamers, the knee draggers and the rain

dancers." Awesome.

"About the Author" was a hoot! LOL.

The Kink! It bit me hard once, running the 24-Hour on a Suzuki GT750 (!), think it was '71, attention diverted by a photographer IN A BRIGHT RED SHIRT! Ran straight off, thought I had it till the third buck, then up into the classic flying W and over the bars. We still got 4th in class. Seems so long ago, but it's only been 45 years.