The Great Escape, or: Hey, Weren't Those the Rocky Mountains?

"Temperatures are expected to top out over 100 degrees (38C) today," drawls an unenthusiastic voice on the radio. "There's an overturned tractor-trailer downtown and a four-car pile up on the Hollywood Freeway has traffic at a stand-still all over LA."

"Great," I remember thinking to myself. An idea pops in my head, and the telephone beckons. I dial.

Ring.

Ring.

A familiar voice answers: "Hello?"

"Hey Pete, let's go to Colorado."

"We're there, dude."

And so it began -- in the midst of a heat wave -- the start of this, a two-week journey that would cross seven states, five National Parks, 3500 miles (5600 km), and not one traffic jam or a single ticket-waving, revenue-generating policeman.

Here's What We Planned:

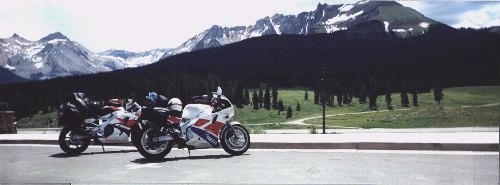

Our mounts for this journey would be a 1994 Honda CBR900RR, and a 1989 Yamaha FZR1000. Not what the manufacturers had in mind as touring bikes, mind you, but when you have a hankering for the twisties, there's nothing like a mega-sportbike with saddlebags to burn up some asphalt.

Our route would take us the fastest way out of this hell hole known as Los Angeles, CA -- we'd make a beeline for bland old Interstate 15 (a major four-, five- and six-lane freeway), and straight into Utah, where the real riding would start. Once we got off the superdrone expressway at St. George, Utah, we wouldn't see another straight road for the next 2000 miles (3200 km)!

Riding due east would take us through the southern half of Utah, and into Colorado for a couple days in Durango -- the mountain biking headquarters of America. Then up to the northeast corner of the state where we would camp for a night in the Rocky Mountain National Park, and northwest through Wyoming to Yellowstone National Park, where the deer and the buffalo roam for Independence Day weekend. Our plan was to either build a house in any of the National Parks and stay there for the rest of our lives, or head south out of Wyoming into Utah, following back roads that parallel the interstate to St. George, then back to Los Angeles.

Sounds like fun, eh?

But Here's How it Really Happened:

Taking off in the middle of a heat wave, which we did one shitty afternoon, wasn't such a good idea. We hit Las Vegas, Nevada -- due East of Death Valley, CA -- in the middle of the afternoon, and a cheesy neon thermometer showed 120 degrees (49 C). It may as well have been 220 (bloody hot): Decked out in jeans, boots, leather jacket and gloves, we were on the verge of passing out. Pete and I stopped for gas and three gallons of Gatorade each, then completely soaked our hair, shirts and jeans with water from the rest room's sink. The jeans were dry in the first couple of miles, but the our hair and shirts provided relief from the desert's furnace for quite some time.

We'd hoped to soldier on through the heat and into Zion National Park to camp the first night, but the heat and frequent stopping to re-soak our clothes meant that by the time we reached St. George, 395 miles (630 km) from Los Angeles, we were ready for a cold shower, a swim in a tub of ice, and bed. We found a motel that could provide everything but the tub of ice and checked in. Their pool was a close substitute, so we floated around in it for a while, unwinding from the road, completely exhausted but excited about what the rest of the trip was going to be like.

By seven o'clock the next morning, it was already over 80 degrees (27 C). What was supposed to be a leisurely vacation turned into a race to get away from the heat wave and up into some real elevation.

State Route 9, off US 15 a few miles north of St. George, meanders its way past three different creeks, and through five small towns while climbing about 3,000 feet before stopping at the entrance to Zion National Park. A toll booth will grab two US dollars from each motorcycle in exchange for an information booklet about the park, a smile from Mr. (or Ms.) Ranger, and access to the park. The fee is also good for as much camping, and as many trips into and out of the park as can be done in one week.

Zion is a visually-spectacular park with seemingly-unnatural rock formations, arches, and sheer vertical cliffs. The roads are well-kept, though somewhat narrow and sandy. About a mile into the park is a mile-long tunnel through solid rock, barely wide enough for two cars to pass each other. As we neared the entrance, traffic was being stopped to allow an over-sized camper to come through from the other direction, and we used the break to cool off under a rare shade tree and suck down more water.

The road through the park is 14 miles (22.5 km) long and it takes about an hour to reach the other end. Speed limits are "strictly enforced" but with all the lookey-loo's (ourselves included), speeds never get high enough for anyone to enforce. Probably why we never saw any type of law enforcement there.

Once clear of the Park, State Route 9 ends 15 miles (24 km) later at US Route 89. For the next 50 miles (80 km) the road opens up and gently climbs to about 6000 feet before dropping into a valley on its way to Bryce Canyon. One side of the road follows the Virgin river, and lush green farm-land lines the other. The rolling hills are small and the curves are graceful and flowing. It felt good to open up the bikes after the crawling speeds through Zion.

The north end of State Route 12, just a few miles out of Bryce, is beautiful. For about 40 miles (64 km) it climbs a tortuous path through Dixie National Forest at elevations of up to 9200 feet, offering panoramic views of the desert floor far below. The wildlife must like it here too, as colorful flowers and grass-covered hills give way to a dense pine forest at the summit. Route 12 ends about 15 miles (24 km) later in the town of Torrey, where it meets State Route 24. With a population of about two, the town bird is the mosquito, and public transportation is the back of someone else's pick-up truck. We were surprised to find a mini-mart there, like the ones that infest big cities, so we stopped for food and more water. It was getting late, so we covered the 15 miles east to Capitol Reef National Park in about 10 minutes riding along the ancient bed of the Fremont River.

Later that evening, as we were firing up the camp stove for a dinner of noodle soup and a cup of coffee, one of the kids from a neighboring camp site approached us.

"I remember you guys. We saw you in Bryce this morning. This bike is yours, and that one is your long-haired friend's." And with that, he was gone. Funny what kids remember after looking out the back window of a mini-van for thousands of miles.

If you're paying attention to your map, you'll find Utah's State Route 24 meets State Route 95, 35 miles (56 km) east of the park. The Bicentennial Highway travels through a desert southeast to Blanding and US 191. North about 35 miles to Monticello, and you meet US 666, appropriately nicknamed the Devil's Highway.

Crossing into Colorado, the landscape changes to rolling grass-covered hills and farmland. A sign posted at the entrance Dove Creek welcomes all that pass to the Pinto Bean Capitol of the World. Oooh, exciting! Far in the distance are the snow-capped Rocky Mountains, standing guard over America's great plains, and calling loudly to a couple of city-weary sport-bike enthusiasts.

Two nights in a hotel in Durango blew our accommodations budget for a few days, so the next two nights would be spent in a sleeping bag. Back-tracking west a few miles took us to the road to Telluride, State Route 145, which was the start of some real riding. The next 65 miles (100 km) were spent wearing out the edges of our tires as the elevation steadily climbed to 10,222 feet at Lizard Head Pass, then dropping us at the doorway to Telluride, a beautiful town for the beautiful people (rich, that is). Telluride is backed up against a box-canyon, with nothing but switch-back infested Jeep trail leading to the top. There are no traffic lights in Telluride and pedestrians roam the streets without fear. It is definitely a tourist town, getting all it's money in the winter ski season, but summertime is for the locals. Nestled high in the mountains, it's quiet and simply beautiful. Since living in a National Park is illegal, Telluride got our vote as the next best place to live.

At Placerville, a right turn on State Route 62 takes us back to US 550, which is the road out of Durango we detoured around to get to Telluride. More beautiful scenery, incredible elevations, perfect motorcycling roads, and we get to US 50 that leads us to Gunnison and over Monarch Pass, the highest point of our trip. A view of the entire country seemed possible as we approached the 11,312 foot pass over the Continental Divide (the point where rain waters divide on a continent). Then down to Poncha Springs for a night in a desolate campsight next to the Arkansas River, deserted except for the eerie sounds of freight trains slowly winding their way along the tracks on the oposite side of the river every couple of hours. The trains were so long, and the gorge they were following so twisty, that the engines would be out of ear-shot long before the rest of the train disappeared, and what we heard were the cars' wheels grinding and howling like ghosts in the night as they played follow the leader into the dark. We roasted marshmallows and imagined what the Indians must have thought a hundred or so years ago about the white man's evil-spirited iron horses.

The next night we would reach Rocky Mountain National Park, and that's when it looked like our plans would all come unraveled. We had planned on spending two nights here with a day's hiking in between. That was, until the ranger at the west entrance to the park warned us that all the campgrounds were full. We had just ridden about 200 miles (320km), the last 50 or so (~80km) at a snail's pace through the park, it was getting dark, and now it looked like our plans to camp here for the next couple of days were about to go up in smoke. Here it was, the Thursday before the long July Fourth weekend and all the campsites at one of the most popular parks in the country were full. Who'd of thought?

The trip through the park offers one of the most spectacular views anywhere. The entire park is above 10,000 feet with some peaks reaching over 14,000 feet. There are a few glaciers on the north side of one of the peaks, and most of the road is above the timberline. As the road climbed in elevation, the once tall pine trees grew increasingly smaller until, right at some pre-determined elevation know only to them, they were no more than small shrubs. Eventually, nothing but tundra grows in the high thin air. The funniest thing to see was that almost every car, and more than a few of the touring bikes, all had someone there to stick their head out of the sunroof or stand up on the pegs, looking at the whole park through the viewfinder of a video camera.

Fortunately for us, one of the many campgrounds there was reservations-only and after checking in with the reservations desk, it looked like there was a no-show that day. We could have it for the night, but we would have to move on in the morning. Feeling very fortunate, we found our spot and unpacked the bikes staking our claim on the small piece of ground. A nice Italian dinner was waiting for us in Estes Park, a small town similar to Telluride in ambiance, but more populated due to its proximity to Denver and the National Park. Have you ever tasted water from a public drinking fountain that actually tasted good? I mean really good? Estes Park is full of them, along with a small fresh snow-pack-melt river running through and around a shopping center complete with a paddle wheel that actually worked.

With the problems we had getting into Rocky Mountain Park on Thursday, and knowing it was a two day ride to Yellowstone National Park, we were more than a little worried. What would it be like trying to get a campsite in one of the country's most popular parks on a Saturday night in the middle of a long holiday weekend? It certainly seemed impossible, but as we couldn't stay where we were, we had no choice but to move on.

Rather than go back through the speed-impaired park to get to Wyoming, we went east to Loveland, north to Ft. Collins, then west on SR14 to Walden. Keep an eye out for Sleeping Elephant rock along this road. Whether or not it's just the power of persuation from reading the sign, this thing really looks like an elephant had been carved into the side of a mountain. It's uncanny.

Leaving friendly and beautiful Colorado, and passing into barren Wyoming, the feeling of being in another country, where travellers aren't taken kindly, was a sign that we'd probably just been on the road too long. Either way, the scenery did go rather flat all of a sudden. There were signs pointing to little nubs in the ground that were actually the Continental Divide. A major contrast to the majestic Monarch Pass of a few days ago.

Another 300 mile (480km) day and we spent the night in Rawlins at a somewhat less than salubrious hotel. The temperature had come up again and the first reason for picking this hotel was their pool. When we jumped in it and found out the heater didn't work, and the water was about, oh, 40 degrees (4.5C), we should have left right then. But there was a clothes washer and dryer right outside our room and we were short of clean clothes and long on laundry. There was also an empty bar with a pool table.

Three hundred more miles (480km) along SR287 and we arrived at the south entrance to Grand Teton National Park, which doubles as the entrance to Yellowstone National Park. Again we were fortunate in that the signs inside the park indicated that not all of the campgrounds were full. The nearest available site, Grant's Village, was about 60 miles away (96km), about an hour and a half doing the speed limit, but by the time we got there, they had put up a sign saying they were full. Not ones to believe everything we read, and hoping maybe to bribe someone out of a place for the night, we sweet-talked the campground ranger into letting us stay in one of the sites reserved for large groups. We could even have it for as long as we wanted. We thought for sure we had used up all our luck on this trip by now, but would find out later that there was a little more in store.

The next two days were spent in the lap of luxury. About a mile from our new home was a fabulous restaurant overlooking Lake Yellowstone. One side of the building was floor to ceiling glass with a view that just didn't stop. Excellent wines complimented deliscious main courses, and their mud pie desert was the reason we came home about 10 pounds heavier than when we had left. It was in the middle of one of these heavenly ice cream and cookie delights that, as if on cue, a deer and her fawn strolled leisurely across the patio just outside the twenty-foot-tall wall of glass. All thoughts of Los Angeles no longer existed. This, we knew, was what life was supposed to be like.

We stayed in Yelowstone for three nights, leaving reluctantly on Monday, July Fourth for what would be a three day trip back to L.A. Everything about Yellowstone made us want to stay. The tree-lined roads, scenic lakes, rivers, and waterfalls competed for our attention with the abundant wildlife. We saw many buffalo throughout the park, and they seemed to enjoy the warmth of the sulpher pools, as they could often be found soaking in the rancid stuff. It was easy to tell where there were deer or elk within sight of the main road -- just look for all the minivans parked in the middle of the road, cameras at the ready. We were almost taken out by a young moose who decided to cross the road right in front of us in one secluded area of the park. This "baby" was at least eight feet tall at the shoulders, and just came prancing out of the forest like he owned it, and disappeared after a few feet into the woods on the other side. We slowed down no problem and just stared after him for a few minutes in amazement. Thanks to our fore-sightful fore-fathers, there are places in this country where these animals can be free to roam without the threat of being senslessly slaughtered.

Highway 89 south out of the park meanders through Teton National Park, and Jackson Hole Wyoming, which has the dubious distinction of housing the worst restaurant of our trip, and through the southeast corner of Idaho, before leading back into Utah. That night in a hotel near Salt Lake City, the local weather report made mention of three inches of snow that had fallen at Yellowstone's airport that day. What luck! The weather for the entire weekend we were there had been beautiful, sunny and warm, Tee-shirt and jeans kind of days you might expect in Southern California.

The next two days were rather uneventful, and knowing our trip was almost over, our moods were sinking fast. Fortunately the trip back through the deserts of Nevada and eastern California were not as hot as before, but one thing was for sure: The traffic certainly hadn't improved while we were gone. About 60 miles (100km) outside L.A. and the traffic had come to a stop. Six lanes of freeway in either direction and cars were stopped. Time to go back to splitting lanes, and dodging sleeping drivers.

It seems as though people living in large, very large, cities get so used to the way things are, the killing, looting, riots, traffic, and sky-high cost of housing, that they become immersed in it and forget that there are places all over the rest of the world that are so far from what they've become used to, that those places all seem like a dream, unobtainable or even non-existant. Sure, coming back from these places is always depressing, but tasting the freedom from the rat-race even for a couple of weeks, lets you cope with the big city, for a little while longer. Until they make it legal to live in National Parks.

More by Mike Franklin, Road Test Editor

Comments

Join the conversation