Into the Cherokee Nation

The roads that wind around the mountains of northwest Georgia are not as traveled as the more famous roads in the northeast, the ones that give access to the Great Smokies.

The asphalt in the northwest corner of the state is slightly tamer than in the east, less frantic. It's also less covered with sport bikers trying to prove their manhood and with travel trailers chugging down the road like large metal tortoises. So your riding is less "interrupted." The highways around here, especially Georgia Highways 52 and 53, still offer excitement, but the ride can be pleasant or challenging, depending on your speed. There are enough surprise decreasing radius curves that you need to ride at about 80 percent so you don't get caught with less road than you need. For these roads I recommend a bike with good, stable handling, one that encourages you to strafe corners like a Spitfire going after a German E-boat.

This part of Georgia was all once part of the Cherokee Nation, an independent nation within the boundaries of the United States. The nation was established by treaty with the U.S. in 1819. In its brief existence, it included parts of four states. (The map is courtesy of cherokeehistory.com.) The Cherokee Nation (outlined in red) was less than a tenth of the lands that the Cherokees had once controlled (the larger grey outline). Their lands when the white man arrived had covered more surface area than many historical kingdoms that we now call "empires." Parts of seven states once fell under control of the tribe (eight, if you count West Virginia, which wasn't established until 1865).

There's not much of anything at the foot of the ramp, just the ability to turn left or right. Go right. In a couple of miles, you'll see a golf course on the left. Slow down and turn right into the New Echota State Historic Site.

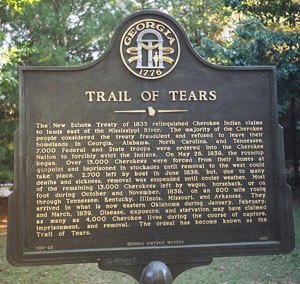

Usually only a few visitors are at the site at any one time. Guilt may have something to do with that. I told you there were sad stories in these mountains, and this place is the key to what may be the saddest. Highway 225 is the Trail of Tears Highway. Here at New Echota one of the biggest dreams in this nation's history was born. In the fall of 1819 the Cherokee Council began holding meetings in Newtown, near the center of their new nation. In 1825 they renamed Newtown and called it New Echota. If you walk the grounds, several structures dot the landscape, some original, but mostly reconstructions. Here was their legislature, their supreme court, and their printing press, which printed The Phoenix, the first native language newspaper ever printed in the United States. Smart lads, the Cherokees. Their great scholar, Sequoyah, who had no formal schooling, figured out how to write their language down. It took him twelve years, but he did it. He is the only person known to have single-handedly created a written language.

New Echota was the site of the Cherokees final "defeat." It wasn't a military defeat, rather a recognition on the part of some of the Cherokees that the whites would eventually take all of their land. Here the leaders of the minority "treaty party" of the Cherokees signed the Treaty of New Echota, which surrendered all of the Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi River in late December, 1835. (The "treaty party" did not represent the majority of the tribe. In fact, the leaders of the treaty party were later assassinated by other Cherokees.) In 1836 the treaty was ratified by the U.S. Senate by a one vote majority and over the objection of Daniel Webster. President Jackson gave the Cherokees two years to vacate their land. Most refused. In 1838, seven thousand state and federal troops arrived to enforce the President's order. The Cherokees were rounded up in stockades, one of which was Fort Wool, located at New Echota. So the town gained another historical note, the Trail of Tears began here. The journey was arduous for the approximately 15,000 Cherokees who went to Oklahoma. Along the way, it is estimated that 4,000 members of the tribe died, though no one is exactly sure of the count.

When you leave New Echota, continue about fifteen miles north on 225 to Spring Hill, another famous Cherokee piece of history. Here you'll find Chief Vann's residence, a two story plantation mansion built of red brick. Completed in 1804, it has been called the "Showplace of the Cherokee Nation." His house is a shock to many white visitors who don't realize how successful many Indian businessmen were. From here Chief Vann ran his many endeavors.

He was a wealthy man with hundreds of acres of land. His favorite hobby was horse racing. Around the house are some of the original outbuildings along with a few that have been moved here to replicate what this site might have looked like when Chief Vann was in residence. His immense land holdings fell into the hands of whites after his son, Joseph, was forced to leave for Oklahoma in 1835. Joseph Vann was evicted by the Georgia Militia after unknowingly violating a new state law barring Indians from hiring white men. "Rich Joe" Vann died in a steamboat explosion in 1844.

From Chief Vann's house, head east on Highway 52. This highway leads you back into the mountains, becoming more challenging as you climb. Now it's time for some serious riding. You should get both sides of your treads nice and toasty. This stretch of Highway 52 will rival anything in the state as it climbs up to Fort Mountain State Park. Even past the park the road stays good, provided you are lucky enough to avoid clumps of traffic or have them show up where the state has been kind enough to give you a passing lane. Riding two up, we got caught behind a couple of slow sport bikers who were riding one up.

Thankfully, a passing lane appeared and we blew by them on the inside. My wife's unsolicited "Wheee" from the intercom assured me that she really didn't notice how close my knee was to the pavement. Past the apex, I started to feed in more torque. Damn! I love v-twin sport bikes.

Fort Mountain is one of the most curious state parks in Georgia. It contains a mystery which no one has ever solved. An 855-foot-long rock wall partially encircles the summit of the mountain. The rock wall faces the gentler slope approaching the summit from the south, and apparently served a military function, since the steeper approach (from the north) has no wall. Its construction has been attributed to a variety of people. Some think that the Cherokees constructed it as a defensive formation or a ceremonial site, but that conclusion is disputed since they usually worked in wood, not stone. In the 16th century, Hernando DeSoto visited Cherokee land.

Some theorize that his men built the stone fort, but they weren't in the area long enough to do it. Another story of the wall's construction comes from the legend of Prince Madoc, a Welsh prince who fled Wales in 1180 with two shiploads of his adherents. He supposedly landed at Mobile Bay in Alabama and moved northward with his men. Those who favor this theory say that they built the fort, then his people disappeared as they intermarried with the Indians. A fourth answer comes from Cherokee legend, which tells of a prehistoric white race, whom they called the "moon-eyed people." Supposedly predating the Cherokees, these people had blond hair and blue eyes. They had keen eyesight in the night, but were almost blind in the full sun. The Cherokees eventually overcame them. Perhaps these people built the wall, but no one really knows.

Regardless of the varied theories of construction, a Cherokee medicine man told me that some modern day Indians still consider the mountain to be a sacred place, which implies that the white man had little, if anything, to do with it. His comments suggested that Fort Mountain had been a ceremonial site for the Cherokees for generations before the arrival of the first white men. Fort Mountain State Park is also one of Georgia's most complete state facilities, with seventy campsites and fifteen cottages available to rent. It

The mount for this ride, my Buell XB12Ss.also contains a lake, additional hike-in campsites, and trails for both mountain biking and hiking. But its facilities are not as complete as those of Amicalola Falls State Park, built around a tumbling waterfall that drops down a 700 foot slope. This park, also accessed from highway 52, has even a wider range of facilities, including a guest lodge. (For more information on these parks, go to http://www.gastateparks.org/.)

From Dahlonega, State Highway 60 will take you back to Highway 400, which will speed you back to Atlanta. Once you depart Dahlonega, you will still cross over parts of the old Cherokee Nation on your return home, but their footsteps have been erased by the larger footprints of the white men who took their land. But behind you, deep in the forest, at odd places like Fort Mountain, New Echota, and Spring Place, the Cherokees have left remnants of what was once a thriving culture. When I look back at the trail of broken treaties with the Cherokees, I am reminded of the quip from Will Rogers, "Yup, I'm mostly Cherokee, just got enough white blood in me to cause you to doubt my honesty."

Comments

Join the conversation